In the previous two posts, we ran through an intro to Indexing on Solana, then discussed Geyser.

In this post, we’ll run through our architecture, including:

High-level validator setup

Message Broker

AccountsDB database

Disaster Recovery

Results Recap

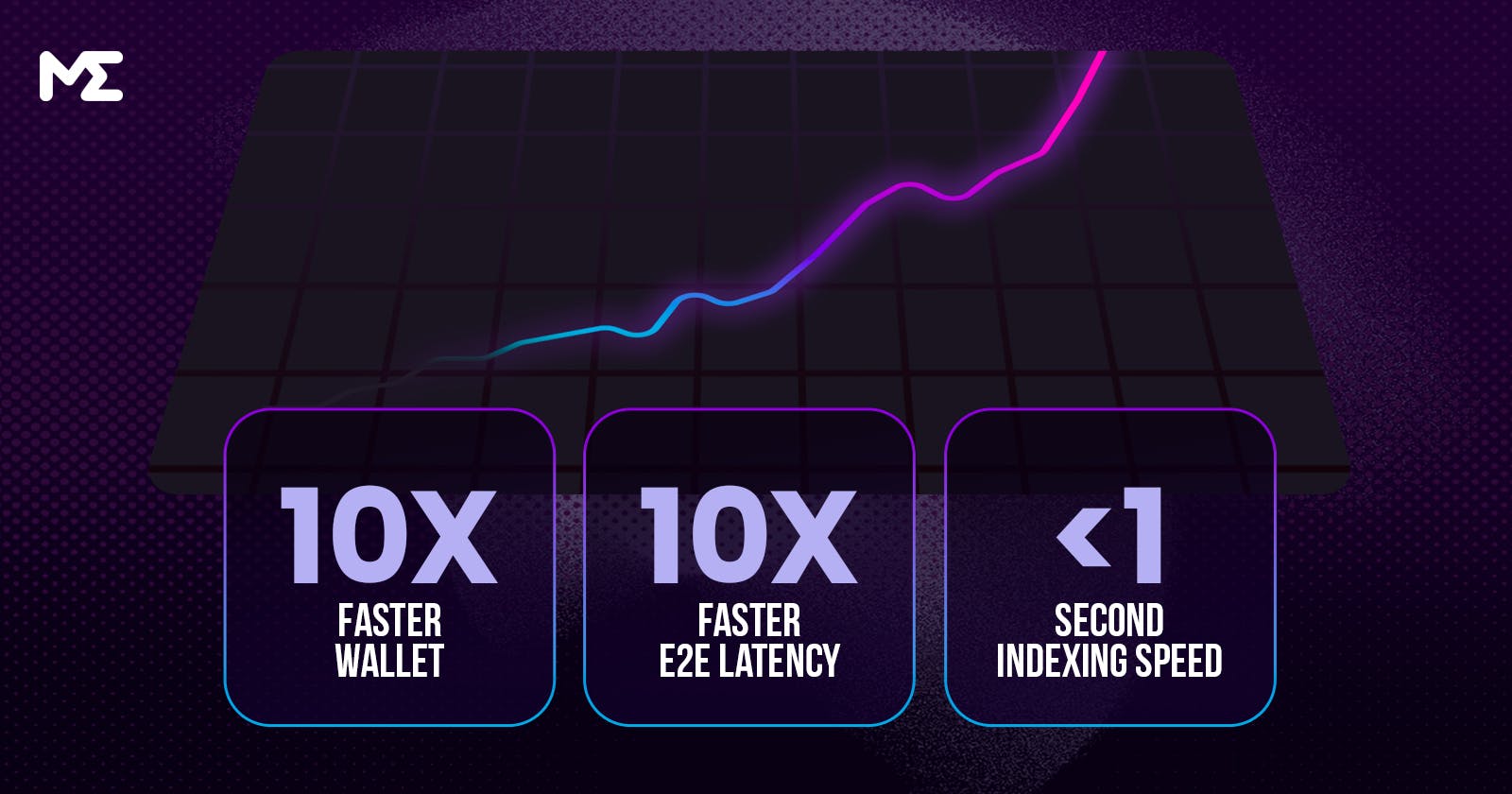

In migrating to Geyser-based indexing, Magic Eden’s performance has improved from several angles, including freshness (how long does it take an update to make it from confirmation to the DB) as well as read performance (RPC-less reads, custom indices).

We’ve cut down our indexing speed to <1s at p95 from upwards of 20s+

Reads have also dramatically improved around the board:

10x faster wallet and collections page loads

10x faster e2e latency (duration from a user seeing a transaction succeed to when our site reflects this information)

Significant cost savings

Architecture

From a high level, our indexing stack breaks into four parts:

Validator / Geyser Plugin - We run our own validators with a custom Geyser plugin, streaming various updates (including accounts) to our message broker.

Message Broker (Kafka) - Using a message broker decouples our validator from our downstream consumers/datastore, bringing increased reliability/scalability. It also gives us the ability to replay messages from a recent offset in the case of an outage. We went with Kafka for this.

Indexers - These are consumers consuming from Kafka, applying certain filtering and transformations, then upserting to the database.

Database (Postgres) - Read-optimized views of on/off-chain data. This is constituted of both normalized Solana account data, as well as denormalized entity tables (like NFT).

Validator & Geyser

We’ll run a deep dive into how we run our validators in a future post. But generally speaking, we’ve found it most reliable to run our validators with as little responsibility as possible, focusing on writing to our message broker as quickly as possible. To this end, we:

Serve no RPC traffic, as this can slow down the validator

Turn off voting/staking

We also enforce certain rule-based gating in our Geyser plugin to filter down the firehose of accounts coming from chain. If we assume 3600 TPS at a given moment, with 1-10 mutable accounts being involved in each transaction, we can be receiving anywhere between 3k to 50k account updates per second. With our filters, we end up sending through a more manageable ~300-1k updates per second that we’re interested in.

For example, if we were only interested in indexing Token account ownership data, we can add a filter in Geyser for the Account.owner=”TokenkegQfeZyiNwAJbNbGKPFXCWuBvf9Ss623VQ5DA”

This reduces the number of account updates coming from Geyser drastically (80%+). We could further reduce this if we cared about a subset of token types. For example, if we only cared about tracking wallet balances of SOL on-chain, we could do the following:

static TOKEN_KEY: Pubkey = solana_program::pubkey!("TokenkegQfeZyiNwAJbNbGKPFXCWuBvf9Ss623VQ5DA");

static SOL_MINT: Pubkey = solana_program::pubkey!("So11111111111111111111111111111111111111112");

fn update_account(

&mut self,

account: ReplicaAccountInfoVersions,

slot: u64,

is_startup: bool,

) -> Result<()> {

let ReplicaAccountInfo {

pubkey,

lamports,

owner,

executable,

rent_epoch,

data,

write_version,

} = *acct;

if owner == TOKEN_KEY.as_ref() && data.len() == TokenAccount::get_packed_len() {

let token_account = TokenAccount::unpack_from_slice(data);

if let Ok(token_account) = token_account {

if token_account.mint == SOL_MINT.as_ref()

{

this.publisher.write_account_to_kafka(UpdateAccountEvent {

account,

slot,

is_startup,

tracing_context: get_tracing_ctx(&|| self.now()),

})?;

}

}

}

}

This checks if the account is a part of the Token program, and if so, deserializes the account, publishing the account update to Kafka if the account’s mint address matches the SOL token.

Doing this kind of filtering in your Geyser plugin dramatically reduces the amount of data you need to handle downstream.

Kafka as a Message Broker

While async processing of messages via brokers like Kafka is fairly common practice in large-scale distributed systems, it’s still worth touching on here.

Message brokers allow the decoupling of various parts of a system - in this case, the decoupling of the validator and downstream indexers. Kafka has given us:

Better performance - Geyser will not be blocked by how quickly we can index updates

Increase Reliability - Message consumer can handle database failures downstream

Throttling - Can smooth out large bursts of messages in times of high TPS load

Disaster recovery - If writes fail, or the database goes down, we can decide to block consumption until recovery is complete, or reset the offset to an earlier time to re-index account updates

We use Kafka for 95% of our message handling. It comes with the following benefits:

Scalability: Kafka is designed to handle a very large volume of messages, making it suitable for use in large-scale systems. It can also be horizontally scaled by adding more brokers to the cluster. If it can handle Google’s scale, it can handle ours.

Performance: Kafka is designed to handle a high volume of messages with low latency, making it suitable for real-time processing of messages. It achieves this through several optimizations, such as a highly efficient storage format and the ability to process messages in parallel using multiple consumers.

Reliability: Kafka stores all messages that pass through it, allowing consumers to read messages at their own pace and providing a record of all messages that have been sent. This makes it possible to build fault-tolerant systems that can recover from failures.

Flexibility: Kafka supports a wide range of use cases, including real-time streaming, data integration, and event-driven architectures. It can also be used to process messages of different types, such as text, binary, or structured data.

Ecosystem: Kafka has a large and active developer community, which has created a wide range of tools and libraries for working with Kafka. Best practices are well known, and many engineers we hire have experience with it.

Our Kafka topology has two levels:

Level 1 contains all accounts given to us from Geyser, received immediately once our validator has seen a new state for an account following a newly processed transaction

We have an intermediary AccountBroker service that buffers the account updates until they reach confirmed status or better. We do this because we’d like to only persist the confirmed state of each account in our database. Handling the confirmation in the first level is convenient for the layer 2 indexers. Having a single topic for Geyser updates also limits the logic in our Geyser plugin - beyond basic filtering on program type, all Geyser needs to do is write to Kafka. This saves resources for the validator to keep up with the network.

Level 2 contains only confirmed account updates, and splits them up by priority and account type

Account-Specific Indexers

The AccountBroker service routes each confirmed account to account-specific topics based on the program owner and the account discriminator. Splitting into homogeneous topics allows our indexers to crunch through Kafka backlogs in large batches (instead of 1 write per account), easing the load on our DB. It also allows us to scale up and down individual consumers for more efficient resource consumption.

Each indexer provides extension points for custom hooks - in case we’d like some additional work to be performed before or after indexing a certain set of accounts.

Postgres

Early on at Magic Eden, we stored much of our application data in MongoDB. Mongo had plenty of benefits - it’s quick to develop on, quite flexible, and horizontally scalable.

However, for our on-chain indexing re-write, we decided to run with Postgres instead of MongoDB due to the following limitations we encountered with Mongo:

Scalability: While MongoDB is known for its horizontal scalability, it’s sometimes unsuitable for extremely large datasets or high write workloads. This is because MongoDB's write performance can decrease significantly as the dataset size grows.

Data Consistency: MongoDB's default behavior is to prioritize write availability over consistency. This means that if multiple writes are happening at the same time, it's possible that some writes will succeed while others will fail. This can lead to data inconsistency issues if not handled properly.

Query Language: MongoDB's query language can be quite different from traditional SQL-based databases. This means that developers may need to learn a new query language and new syntax in order to effectively use MongoDB. The ramp-up for many of our new engineers was daunting with Mongo’s query language. This made it easy for us to write suboptimal queries, compounded by our fast-shipping culture.

Schema Design: MongoDB's flexible schema can be a double-edged sword. While it allows for flexibility in data modeling, it can also lead to schema design issues if not planned properly. We found that we skipped out on proper schema optimization and planning due to the flexibility the document model provided us. Additionally, this flexibility made it more difficult to enforce data constraints and ensure data consistency.

Transactions: While MongoDB does support transactions, it may not be as robust as other databases like Postgres. This can lead to issues with data integrity and consistency in certain use cases.

As a result of these drawbacks, we ended up going with AWS Aurora PostgreSQL, a decision we have been quite happy with.

One great feature we got from Postgres was conditional updates. With 1000+ account updates per second, there’s a major potential for race conditions for a single account write. Even while sending each account to a deterministic Kafka partition, there’s a potential to get updates for the same account out-of-order.

Fortunately, the Geyser maintainers included two pieces of information to help synchronize writes for a single account: slot and writeVersion

Slot - The slot at which this account update has taken place

WriteVersion - A global monotonically increasing atomic number, which can be used to tell the order of the account update. For example, when an account is updated in the same slot multiple times, the update with a higher write_version should supersede the one with a lower write_version.

With this information, we can run conditional updates:

This allowed us to guarantee consistency, while still writing updates to the database efficiently in batch.

Disaster Recovery

Disaster recovery is a crucial aspect of any system, and our Solana indexing pipeline is no exception. We understand that various types of failures can occur throughout the pipeline, including validator downtime, Postgres writer node unavailability, and data corruption due to retries or deadlocks. While we have implemented measures such as retries and Dead Letter Queues (DLQs) to mitigate these issues, data corruption is still a possibility. Therefore, it's crucial to have a comprehensive disaster recovery plan in place to ensure the integrity of our data in the event of a failure.

We have three primary mechanisms to restore our DBs in the case of a major outage:

Restore DB and Replay

We can restore our Postgres Aurora instances from backups taken once a day (go back in time), then reset our Kafka consumers to an earlier offset, effectively replaying the updates hitting the DB from the time of the snapshot until now.

We would use this strategy the more recently the snapshot was taken. Scaling out our indexers for this only takes a few seconds (as quick as Kubernetes can bring up new pods)

Truncate DB and Backfill

If our snapshot is sufficiently far back in the past, we can make the decision to truncate the problematic tables, then run a backfill via our on-demand backfill validator. This validator starts up, emits all (filtered) accounts we’re interested in via its startup snapshot, then exits.

This method takes longer than Restore and Replay - backfilling all token accounts on Solana (100s of millions of tokens) can take a few hours.

Replay Txs and backfill from RPC

The other two methods are akin to hitting the indexing system with a sledgehammer - they both result in downtime and backfill more data than we need to recover from a given issue. They also rely on our validators being functional.

If we’ve missed messages, but haven’t ingested any truly corrupt data - we can also invoke our RPC replayer. This will replay all transactions from the suspect time period, invoking an account refresh from RPC (like Quicknode) for all accounts updated by the transactions, and write the expected data to our index.

This allows us to backfill without any downtime and recover without our validators as a dependency (which may take hours to bring back online in certain situations).

Conclusion

In conclusion - by migrating to Geyser-based indexing, we have achieved significant improvements in performance, reliability, scalability, and cost savings. We continue to refine and improve our indexing stack to provide the best experience for our users. If you have any questions - please feel free to DM us on Twitter. We’re also actively hiring! https://boards.greenhouse.io/magiceden